|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Reader Collection > Exhibitions > Painting Styles Illustrated in 18th and 19th Century Japanese Books

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Introduction In the modern age (i.e., twentieth and twenty-first centuries) examples of different painting styles are readily available to art-lovers from various sources, including the internet, museums, art galleries and books. In contrast, pre-modern art-lovers had only books. In Japan, artists and publishers combined to produce many picture books for art-lovers in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Some of these books illustrated the style of a particular artist while others provided examples of multiple styles. The following six painting styles were illustrated most often: Kanō, Rinpa, Nagasaki, Nanga, Maruyama-Shijō and Nihonga. This virtual exhibition explains the characteristic features of these six styles and provides five examples of each style, chosen from thirty books in the Reader Collection of Japanese Art. This Collection focuses on flower-and-bird art so that is the subject of the pictures chosen for this exhibition. Additional information about these painting styles is available in the following books: Conant, Ellen P., Owyoung, Steven D. and Rimer, J.

Thomas. 1995. Nihonga, Transcending the Past: Japanese-Style Painting,

1868-1968. The Saint Louis Art Museum, St. Louis. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

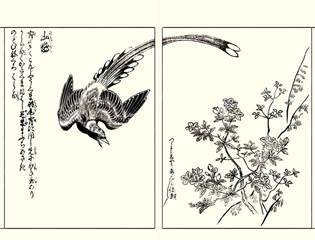

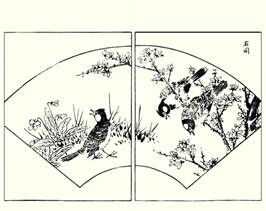

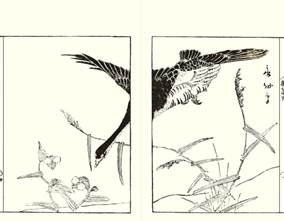

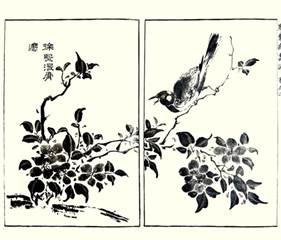

Kanō Style - Kanō is the surname of a large family of painters whose work was supported by members of the Japanese military government starting in the seventeenth century. Kanō artists largely adopted the style of professional artists in the Chinese imperial court because this Chinese style was held in high esteem by their Japanese government patrons. Accurate depiction of shape and color was sacrificed to show the characteristic behavior (i.e., inner spirit) of the picture’s subjects. Distinguishing features of Kanō-style book pictures were the use of a black line to outline an object’s shape and the uniform application of additional colors, if any, across an object’s surface.

|

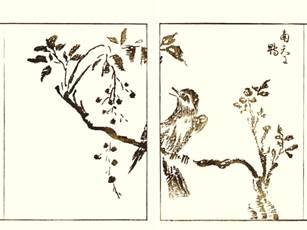

Japanese bush-warbler (Cettia diphone) drawn in the Kanō style.

|

|

||

|

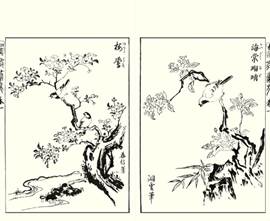

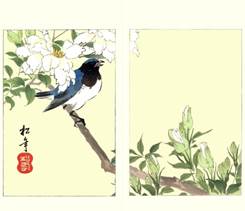

Kanō example 1

Ehon Tsūhoshi (The Hold-All of Sketching Treasures), Morikuni Tachibana (artist), published in 1729

Torch azalea (Rhododendron kaempferi) and blue magpie (Urocissa erythrorhyncha) by Morikuni Tachibana

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Kanō example 2

Gashi Kaiyō (Essentials of the History of Painting), Shumboku Ōoka (editor), published in 1751

Wintersweet (Chimonanthus praecox), violet (Viola sp.) and great tit (Parus major) by Motonobu Kanō |

|

|

|

|

|

Kanō example 3

Honchō Garin (A Grove of Our Country’s Paintings), Sadatake Takagi (editor), published in 1752

Asiatic dayflower (Commelina communis), common reed (Phragmites australis) and white-fronted goose (Anser albifrons) by Motonobu Kanō

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Kanō example 4

Wakan Shūgaen (Banquet of Chinese and Japanese Paintings), Shigenaga Nishimura (editor), published in 1759

Left – Cherry (Prunus sp.) and Eurasian bullfinch (Pyrrhula pyrrhula) by Tōun Kanō Right – Hall crabapple (Malus halliana) and blue-and-white flycatcher (Cyanoptila cyanomelana) by Tōun Kanō

|

|

|

|

Kanō example 5

Gazu Senyō (Selected Essentials of Painting), Gyokusuisai Fujiwara (editor), published in 1766

Peach (Prunus persica) and Japanese waxwing (Bombycilla japonica) by Tan’yu Kanō |

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Rinpa Style - When military leaders took power in the seventeenth century the Japanese emperor and his court were only allowed to pursue cultural activities. Artists who catered to court members reworked art forms from the ancient, golden age of court culture to create a new style of art now called Rinpa. The word Rinpa means school (pa) of Kōrin (rin), referring to Kōrin Ogata who was a major contributor to this new style of art. One distinctive feature of Rinpa art is the artist’s use of curved lines to draw subjects with simplified shapes. Use of rich color is a second distinctive feature.

|

Japanese bush-warbler (Cettia diphone) drawn in the Rinpa style.

|

|

||

|

Rinpa example 1

Kōrin Gafu (Picture Album by Kōrin), Hōchū Nakamura (editor), published in 1802

Little ringed plover (Charadrius dubius) by Kōrin Ogata |

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

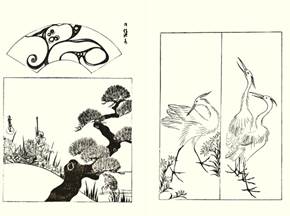

Rinpa example 2

Kōrin Hyakuzu (One Hundred Drawings by Kōrin), Hōitsu Sakai (editor), published in 1812

Left top – water waves by Kōrin Ogata Left bottom – Japanese iris (Iris ensata), pine tree (Pinus sp.) and common snipe (Gallinago gallinago) by Kōrin Ogata Right – Aster (Aster sp.) and little egret (Egretta garzetta) by Kōrin Ogata |

|

|

|

|

Rinpa example 3

Kōrin Manga (Sketches by Kōrin), Kagei Tatebayashi (editor), published in 1817

Left – Bunchflower daffodil (Narcissus tazetta) and white-fronted goose (Anser albifrons) by Kōrin Ogata Right – Common reed (Phragmites australis) and mandarin duck (Aix galericulata) by Kōrin Ogata |

|

|||

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

Rinpa example 4

Kōrin Gashiki (Kōrin’s Style of Painting), Minwa Aikawa (editor), published in 1818

Lespedeza (Lespedeza sp.) and domestic fowl (Gallus gallus) by Kōrin Ogata |

|

|

|

|

Rinpa example 5

Kōrin Gafu (Picture Album by Kōrin), Gessai Fukui (editor), published in 1893

Left – Camellia (Camellia japonica), plum (Prunus mume) and domestic fowl (Gallus gallus) by Kōrin Ogata Right – white-naped crane (Grus vipio) by Kōrin Ogata |

|

|||

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

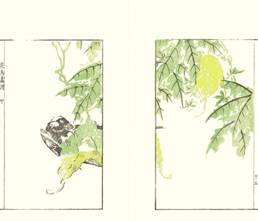

Nagasaki Style - Starting in the seventeenth century military government leaders attempted to reduce potentially disruptive foreign influences by restricting foreign visitors and trade to the port city of Nagasaki. One Chinese painting style imported during the eighteenth century was called Nagasaki to reflect its point of origin in Japan. A novel feature of this style was the virtual elimination of the black outline used previously to define the shape of an object. Instead, shape was defined by applying an area of pigment. Elimination of the black outline and extensive use of other colors made objects look more realistic but not necessarily true-to-life. Typical of Chinese-style painting, the artist’s primary objective was not to reveal a subject’s external appearance but rather its inner spirit.

|

Japanese bush-warbler (Cettia diphone) drawn in the Nagasaki style.

|

|

||

|

Nagasaki example 1

Kanyōsai Gafu (Picture Album by Kanyōsai), Ryōtai Tatebe (artist), published in 1762

Cherokee rose (Rosa laevigata) and light-vented bulbul (Pycnonotus sinesis) by Ryōtai Tatebe |

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

Nagasaki example 2

Sō Shiseki Gafu (Picture Album by Sō Shiseki), Shiseki Sō (artist), published in 1765

Balsam-apple (Momordica charantia) and light-vented bulbul (Pycnonotus sinensis) by Shiseki Sō |

|

|

|

|

Nagasaki example 3

Fukuzensai Gafu (Picture Album by Fukuzensai), Kagen Niwa (artist), published in 1814

Cotton-rose (Hibiscus mutabilis) and silver pheasant (Lophura nycthemera) by Kagen Niwa |

|

|||

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

Nagasaki example 4

Yūsai Gafu (Picture Album by Yūsai), Chikutō Nakabayashi (artist), published in 1846

Bunchflower daffodil (Narcissus tazetta), plum (Prunus mume) and mandarin duck (Aix galericulata) by Chikutō Nakabayashi

|

|

|

|

|

Nagasaki example 5

Kachō Gafu (Picture Album of Flowers and Birds), Katei Taki (artist), published in 1888

Pomegranate (Punica granatum), Japanese banana (Musa basjoo) and light-vented bulbul (Pycnonotus sinensis) by Katei Taki |

|

|||

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

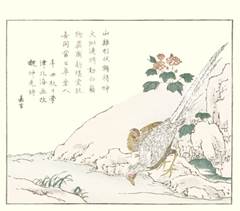

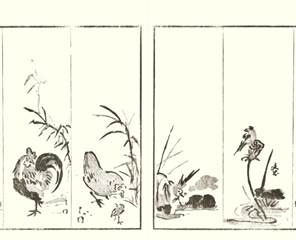

Nanga Style - Another style of Chinese art called Nanshūga (southern [nan] sect [shū] picture [ga]) was also introduced to Japan through the port city of Nagasaki in the eighteenth century. The name Nanshūga was abbreviated to Nanga by the Japanese. Nanga artists used a combination of short lines and areas of pigment to create the shapes of their subjects, as opposed to a continuous line (i.e., Kanō) or only areas of pigment (i.e., Nagasaki style). The resulting shapes appear to be unfinished, more like sketches than completed drawings. This unfinished look was intended to give the impression that objects were drawn in a moment of artistic inspiration. Color was applied unevenly creating blotchy-looking objects and the range of colors chosen was rarely adequate to show objects accurately.

|

Japanese bush-warbler (Cettia diphone) drawn in the Nanga style.

|

|

||

|

Nanga example 1

Bunchō Gafu (Picture Album by Bunchō), Bunchō Tani (artist), published in 1807

Left page – Two views of domestic fowl (Gallus gallus) by Bunchō Tani Right page – White wagtail (Motacilla alba) in left panel and sacred lotus (Nelumbo nucifera) with barn swallow (Hirundo rustica) in right panel by Bunchō Tani |

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

Nanga example 2

Shinki Issō (Clean Sweep of the Mind), Masayoshi Kitao (artist), published in 1814

Heavenly bamboo (Nandina domestica) and brown-eared bulbul (Ixos amaurotis) by Masayoshi Kitao |

|

|

|

|

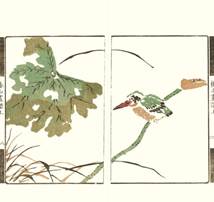

Nanga example 3

Chinzan Gafu (Picture Album by Chinzan), Chinzan Tsubaki (artist), published in 1880

Sacred lotus (Nelumbo nucifera) and common kingfisher (Alcedo atthis) by Chinzan Tsubaki |

|

|||

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

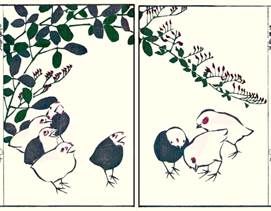

Nanga example 4

Shogafu (Album of Calligraphy and Paintings), Kiyosaku Furusawa (editor), published in 1882

Cherry (Prunus sp.) and Java sparrow (Padda oryzivora) by Kazan Watanabe |

|

|

|

|

Nanga example 5

Banshō Gashiki (Drawing Methods for All Things in the Universe), Unga Tachibana (artist), published in 1894

Common reed (Phragmites australis) and little ringed plover (Charadrius dubius) by Unga Tachibana |

|

|||

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Maruyama-Shijō Style - Dutch traders who visited the port city of Nagasaki introduced western-style art to the Japanese. Illustrations in European books showed objects drawn more realistically than in Chinese art. Shapes were closer to true life and the use of graded, instead of uniform, color created a three-dimensional effect. The first Japanese painter to add these features to Japanese art was Ōkyo Maruyama in the late eighteenth century. Ōkyo attracted many followers, including Goshun Matsumura who started his career as a Nanga-style artist. Goshun combined the impressionism of Nanga with Ōkyo’s realism to create a style called Shijō. The word Shijō refers to Fourth Avenue in the city of Kyōto where Goshun had his workshop. Because Shijō and Maruyama styles are similar the term Maruyama-Shijō is now used to refer to this style.

|

Japanese bush-warbler (Cettia diphone) drawn in the Maruyama-Shijō style.

|

|

||

|

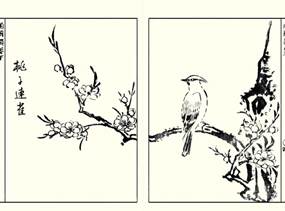

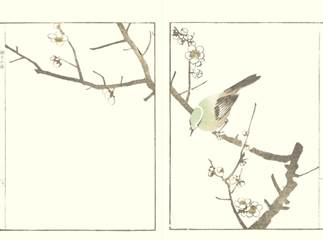

Maruyama-Shijō example 1

Enō Gafu (Picture Album by Old Man Maruyama), Soken Yamaguchi (editor), published in 1837

Plum (Prunus mume) and Japanese bush-warbler (Cettia diphone) by Ōkyo Maruyama |

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

Maruyama-Shijō example 2

Kan'ei Gafu (Picture Album by Kan’ei), Kan’ei Nishiyama (artist), published in 1886

Wintersweet (Chimonanthus praecox) and varied tit (Sittiparus varius) by Kan’ei Nishiyama |

|

|

|

|

Maruyama-Shijō example 3

Seikajō (Refined Pictures of Flowers), Naosaburō Yamada (editor), published in 1892

Pheasant’s eye (Adonis amurensis) and Japanese bush-warbler (Cettia diphone) by Keibun Matsumura |

|

|||

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

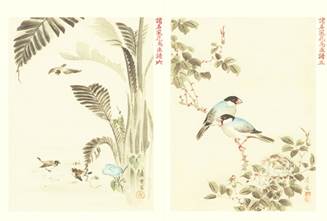

Maruyama-Shijō example 4

Sho Meika Kachō Gafu (Picture Album of Flowers and Birds by Various Famous Painters), Gessai Fukui (editor), published in 1898

Left – Japanese banana (Musa basjoo), Japanese morning glory (Ipomoea nil) and Eurasian tree sparrow (Passer montanus) by Rosetsu Nagasawa Right – China rose (Rosa chinensis) and Java sparrow (Padda oryzivora) by Ōju Maruyama

|

|

|

|

|

Maruyama-Shijō example 5

Nihon Meiga Kagami Tokugawa Jidai Bu (Examples of Famous Japanese Paintings Tokugawa Era Section), Moichi Tanaka (editor), published in 1898

Cotton-rose (Hibiscus mutabilis) and white-fronted goose (Anser albifrons) by Ōkyo Maruyama |

|

|||

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Nihonga Style - In the mid-nineteenth century the Japanese government initiated a modernization program to make Japan the equal of western countries in terms of world power and influence. To achieve this objective government leaders championed all things western, including art. From this program emerged a new style of art that was called Nihonga, which means Japanese (Nihon) Painting (ga). The word Nihon was chosen to distinguish it from Yōga which was the name coined for western (yō) oil-painting. Nihonga artists included some features of previous, Chinese-influenced styles of Japanese painting but emphasized the true-to-life depiction of objects as seen in western art. Nihonga artists paid even more attention to details of shape and color than did the western-influenced, Maruyama-Shijō artists.

|

Japanese bush-warbler (Cettia diphone) drawn in the Nihonga style.

|

|

||

|

Nihonga example 1

Miyako No Nishiki (Brocade of the Capital), Jihee Tanaka (editor), published in 1891

Mandarin duck (Aix galericulata) by Keinen Imao |

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

Nihonga example 2

Kaiga Chō (Album of Pictures), Kanpo Araki (editor), published in 1892

Camellia (Camellia japonica) and blue-and-white flycatcher (Cyanoptila cyanomelana) by Kanpo Araki |

|

|

|

|

Nihonga example 3

Miyo No Hana (Flowers of the Ages), Kōtarō Yamada (editor), published in 1892

Japanese maple (Acer palmatum) and chestnut-cheeked starling (Sturnia philippensis) by Gokyō Kobayashi |

|

|||

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

Nihonga example 4

Bijutsu Sekai (World of Art), Seitei Watanabe (editor), published in 1892

Sasanqua camellia (Camellia sasanqua) and blue-and-white flycatcher (Cyanoptila cyanomelana) by Shōnen Suzuki |

|

|

|

|

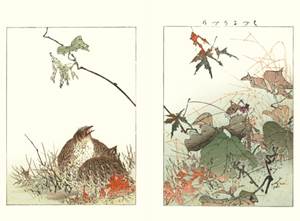

Nihonga example 5

Kachō Gafu (Picture Album of Flowers and Birds), Kōtei Fukui (artist), published in 1896

Kudzu (Pueraria lobata) and Japanese quail (Coturnix japonica) by Kōtei Fukui |

|

|||

|

|

|

|

||